It’s that time of year. Another season has come to an end. You’re taking a brief hiatus from structured training and soon, your thoughts will inevitably turn to base training – those long slow miles that lay the foundation upon which next year’s training will be built.

It’s that time of year. Another season has come to an end. You’re taking a brief hiatus from structured training and soon, your thoughts will inevitably turn to base training – those long slow miles that lay the foundation upon which next year’s training will be built.

What if I said there might be a better way?

Traditional Base Training

The conventional wisdom says base training builds a base level of fitness that will allow you to perform the necessary training later in the build and peak phases so that you may have optimal race performance. Customarily, the base phase consists of high volume at a relatively low intensity that is designed to force physiological adaptations that increase your aerobic capacity. Then, as you move through the season, you move into the build and peak phases where you add intensity and speed work.

I have a couple of problems with that line of thinking.

The Issues

Established fitness – experienced long course triathletes have a base level of fitness and have likely already acclimated to a maximum training volume because they don’t have additional hours available. Many of those athletes have family and career commitments in addition to pursuing their triathlon goals. Training the same number of weekly hours (because they don’t have available time to add more) at lower intensities produces a lower total weekly training stress than they have already adapted to. As a result, the unintended consequence can be detraining.

Specificity – the acknowledged triathlon authority Mr. Joe Friel says that specificity is the single most important principal of training. The specificity principal says, “if you want to be good at something you must exactly and precisely train for its unique demands.” Stated another way, the closer you get to your ‘A’ race, the more like the race your training should become. However, for the long course triathlete, that’s exactly opposite what the traditional ‘base, build, peak, taper’ periodization model does.

A Better Way?

A premise of periodization has always been that you need a substantial aerobic base before your body can handle the higher stress of more intense workouts. Except an experienced long-course athlete has a substantial aerobic base – why would you want to squander that by doing long slow miles that can lead to detraining? Wouldn’t it be better to take advantage of the existing aerobic base and work on strength, speed, endurance AND increasing aerobic base? Recent research suggests that is possible (Burgomaster, 2008; Helgerud, 2007).

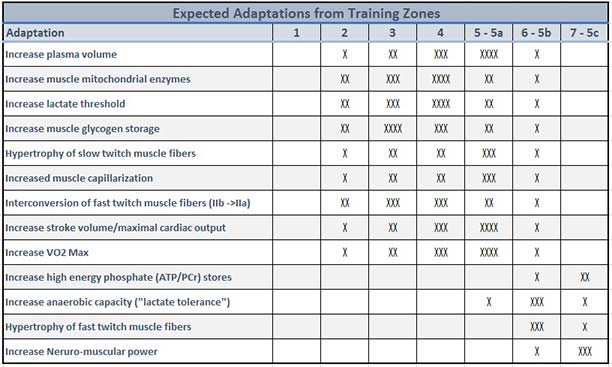

In the chart below, you can see in all but one category, the highest rate of physiological adaptation is forced by training at higher intensities.

One of the arguments against year-round structured interval training is that too much intensity can lead to overtraining. While in days past, that was a valid concern, we now have much better tools, analysis software, and methodologies that more accurately allow us to monitor training stress, fatigue and recovery so the risk of pushing an athlete over the edge into overtraining are much lower.

Case Study in a Different Approach

Ricardo is a lot like many other age-group triathletes. He’s married with a couple of young children and a successful career. Training more than 12-hours a week is rarely possible and a number of times each year, his otherwise tranquil job becomes a monster that demands his time and energy for weeks at a time as the company attends various off-road shows around the country.

This past year, Ricardo wanted to do Oceanside 70.3 in April; his first Ironman at IM Santa Rosa in May which we designated an ‘A’ race; his first Ultra-distance marathon at the Noble Canyon 50K Ultra in September; and the Craft Classic Half-Marathon in October which was also designated as an ‘A’ race. The challenge? His two most relentless periods at work are a few weeks in mid-spring and a month around early fall – right in the middle of the build/peak for his two ‘A’ races. Since we knew going into the season that training was going to be compromised during the final preparation for his ‘A’ races, we turned to an alternative form of base training as the key to a successful season.

When Ricardo goes in to work, he parks his car and goes into the office. However, a bit over two-miles on the other side of the parking lot lies Mt. San Miguel – a 2,567’ mountain. Coincidently, Ricardo would prefer to ride his mountain bike over his road or tri bikes – the more extreme the terrain, the better.

Recognizing that Ricardo had a base level of fitness we decided to take advantage of that fitness. His modified base training consisted of regularly riding up Mt. San Miguel as well as frequent hill work up the same slopes. On the weekend, Ricardo would ride up and over Mt. San Miguel, then around the entire base, and finally back up to the top and down. This wasn’t long slow miles – this was hard threshold and/or VO2 MAX work. We closely monitored training stress, fatigue and recovery state to avoid over-reaching.

As expected, training became very inconsistent during the final prep for the ‘A’ races. Yet, Ricardo set a PR at 70.3 Oceanside. He beat the projections for both IM Santa Rosa and the Noble Canyon Ultra. The two weeks prior to his season ending half-marathon were a study in what not to do leading up to an ‘A’ race – two workouts completed out of twelve scheduled. Coming off of a season of long course racing and several weeks of inconsistent training, that should have led to a DNF. Instead, Ricardo set a PR by over 12-minutes.

Was that season ending PR because I’m a great coach? I don’t think so. Was it because of the unconventional base work? Absolutely!

Summary

Recognizing that you are time-crunched and have likely already acclimated to a maximum training volume is the first step to re-defining base building. For amateur athletes, endurance blocks of two-three weeks should be incorporated into the training schedule multiple times per year. That is far different than a single 2-3-month block of low-intensity riding at the beginning of the season during which you’ll see your FTP and pace at threshold appreciably decline.

Burgomaster, K. A., Howarth, K. R., Phillips, S. M., Rakobowchuk, M., MacDonald, M. J., McGee, S. L., & Gibala, M. J. (2008). Similar metabolic adaptations during exercise after low volume sprint interval and traditional endurance training in humans. The Journal of Physiology, 586(Pt 1), 151–160.

Helgerud J, Høydal K, Wang E, Karlsen T, Berg P, Bjerkaas M, Simonsen T, Helgesen C, Hjorth N, Bach R, Hoff J. (2007) Aerobic high-intensity intervals improve VO2max more than moderate training. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2007 Apr;39(4):665-71.